Francophone economy

This article possibly contains original research. (February 2024) |

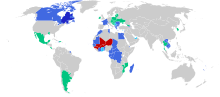

The Francophone economy includes 54 member countries of the OIF, with a total population of more than 1.2 billion people,[1] whose official language or one of the official languages or languages of education is French.

The French-speaking world is often associated with the use of the French language and one of the many French-speaking cultures, but it also has significant economic potential, which remains largely under-exploited, particularly by multinationals, private French-speaking groups and academic researchers, who still publish and communicate with the outside world mainly in English.

This French-speaking world represents a significant economic potential due to the size of its market and the diversity of its member economies. According to an OIF report (2022), the French-speaking economic area accounts for 25% of world GDP, 28% of world trade and 23% of the world's energy and mining resources. The countries of the French-speaking world also include several emerging countries, notably in West and Central Africa, which are experiencing rapid economic growth.

Other areas where French is historically or officially spoken include so called "developed countries" like parts of the United States (particularly Louisiana, New Hampshire, Vermont and Maine), Eastern Canada, Western Europe and parts of Oceania. In addition, member economies of the Francophonie often share similar characteristics, such as colonial history, trade links and common legal practices (for example the Napoleonic Code), which can facilitate trade and investment between these countries. The OIF also provides a political and institutional framework for economic cooperation, for example through the creation of the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA – also officially in French : Zone de libre-échange continentale africaine – ZLECAf) – a free trade agreement between 54 African countries, including many OIF members – or the Eurozone, the European Union, the Comprehensive and Deep Free Trade Agreement and the Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement, all of which overlap with a number of OIF members and share French as a working and official language.

Definition[edit]

To properly define the Francophone economy, a number of factors need to be considered:

- the official language of the country, region or area involved in a trade transaction;

- the language in which goods and services are exchanged (contracts, bank transactions, amicable markets, barter, etc.);

- the official language of the "customer" country, region or economic zone.

Belonging to a common linguistic area tends to encourage privileged trade between countries belonging to this area.[2] Empirical studies, not limited to the French-speaking world, have shown that sharing a common language has a positive impact on the development of trade flows,[3] but this is also true for investment flows and migratory flows.

Cultural proximity, which is fostered by sharing a common language, has a positive influence on trust between economic players, and mutual trust between two countries has a positive impact on their bilateral trade flows.[4]

History[edit]

The historical contours and beginnings of economic relations between French-speaking countries can be traced back to the first official use of French as a language of state and trade (Val d'Aoste, France, Savoie) in the 16th century.

The first intercontinental ensemble took shape with the French trading ports in Quebec and India (17th century). The Compagnie des Indes, the Compagnie du Mississippi and wealthy entrepreneurs (Cavelier de La Salle, Antoine Crozat, etc.) played an important role in concentrating economic exchanges in this new area. Strengthened by the accession (European, Polynesian, then North American) of several countries to the French Empire in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, by the turn of the twentieth century this economic area had expanded to include the African continent and Indochina.

An area such as this can be seen as an economic zone in the making and in its own right; in other words, it is a significant part of the "world economy", linked by multiple relationships (cultural, political, historical, geographical, sociological, etc.).[5] Several initiatives have been set up to promote economic cooperation between French-speaking countries. The Agence de la francophonie pour la promotion des investissements (AFPI[6]) is an organisation set up in 1997 in Abidjan (Côte d'Ivoire) to promote investment in French-speaking countries. AFPI helps companies find partners, obtain financing and navigate local regulations.The Chambers of Commerce and Industry of the Francophonie (CCIF) are another example of organisations that have been promoting economic cooperation between French-speaking countries since the second half of the 20th century. They help companies develop business networks, obtain financing and understand local regulations on a global and local scale.

Since 2013, global organisations and NGOs have been recommending the creation of an Organisation for Francophone Economic Cooperation (OCEF) or an economic operator of the French-speaking world, alongside the historic operators such as the Agence universitaire de la Francophonie, Université Senghor, the Association Internationale des Maires Francophones and TV5Monde. It can also build on the dynamism of groups of "mature" Francophone countries within international organisations such as the OECD. Eighteen member countries of the Organisation internationale de la Francophonie (OIF) are also members of the OECD: Belgium, Canada, France, Greece, Luxembourg and Switzerland for full members (OIF); and Austria, South Korea, Estonia, Hungary, Ireland, Latvia, Lithuania, Mexico, Poland, the Slovak Republic, the Czech Republic and Slovenia for associate members or observers of the OIF.

According to a 2019 projection, the French-speaking world is set to grow to over 700 million daily speakers by 2050, compared with 321 million in 2018.[7]

Potential[edit]

Despite certain challenges (poverty rates in "developing" countries, education systems, customs constraints and freedom of movement) the French-speaking world offers many opportunities. Firstly, trade between French-speaking countries can contribute to their economic growth by stimulating investment and job creation. In addition, economic cooperation can foster the emergence of a middle class in so-called "developing" countries, which in turn can contribute to economic growth. Finally, economic Francophonie can help strengthen the position of more junior French-speaking countries on the international stage by enabling them to speak with a common voice.

On the other hand, with a view to sustainable development, which involves more development markers (HDI) in the economy, it is essential to promote a concerted approach that moves away from the traditional growth markers as theorised from the industrial era onwards in Western countries. The Francophone group can act as a driving force for a different kind of economic action, based on the sustainability and quality of economic and political mechanisms, rather than on pure numerical growth.[8]

In June 2023, the French government proposed a global reform of wealth taxation to forty global leaders and coutries, including Saudi Arabia, China, Brazil and the US.

The potential of business French is shared across five continents and by all French-speaking countries and regions.

In Oceania, for example, the French-speaking world is represented by French Polynesia, Wallis and Futuna, New Caledonia and Vanuatu. Although some of these archipelagos are small island and developing states (or regions), they all have historical and cultural links with the French language.

The economic potential of the French language in Oceania is linked to several factors. Firstly, the French language can be seen as an asset for companies seeking to penetrate the region's markets. French Polynesia and Wallis and Futuna, for example, have tourism-driven economies, and French-speaking tourists represent a significant part of this market.

Secondly, the language can also be an advantage for companies wishing to work with French-speaking national and international organisations active in the region, such as the South Pacific Commission or the Agency for Cultural and Technical Cooperation (ACCT). Finally, knowledge of the French language on all continents can help companies navigate local regulations and administrative procedures, which can sometimes seem complex to foreigners. For the French-speaking world, sharing the language is already creating added value: on average, almost 18% more trade flows are observed between two countries in this area and an average gain of 4.2% in per capita income.

The France-Quebec economic relationship is an illustration: Quebec is by far the leading Canadian province in terms of established French companies, which see it as a gateway to the North American market; conversely, the French partners of Quebec companies make it easier to operate in the European Union markets, providing a unique and privileged economic link between the two continents. In 2023, Quebec City hosted the Rencontre des entrepreneurs francophones,[9] an international meeting bringing together business leaders and economic organisations from over 30 countries.

Financial and economic networks have been created since the beginning of the 20th century to bring together the main French-speaking economic players (banks, major industrial groups, listed companies, industries by sector, etc.).

The OIF summit is an increasingly important forum for economic cooperation between French-speaking countries. The summit meets every four years in a different country and enables ministers and heads of state to coordinate public policies in support of the economies of French-speaking countries.

There is also the Réseau francophone de l'innovation (FINNOV[10]) and the Alliance des patronats francophones[11] (27 membre-states in 2023), which contribute to international Francophone coordination in the private sector.

Yet, despite the need for greater interdisciplinarity in the 21st century, these networks are still struggling to interconnect and interoperate to maximise synergies.

Entrepreneurs[edit]

The use of French in recruitment within international companies is central. A series of ground-breaking studies on the subject, carried out in Armenia, Bulgaria, Cambodia, Kenya, Lebanon, Madagascar, Nigeria, Romania and Vietnam, show the unique place of French in the international job market,[5] particularly in the key sectors of NICT, finance (banking and insurance), education, scientific research, production, trade (import-export), hotels and tourism, as well as careers in the social and political sector (NGOs, international organisations, embassies, etc.), the medical and pharmaceutical industries and construction.[12]

Banking[edit]

On a global scale: the Union des banques francophones (UBF) brings together major players in the sector:

-

Crédit Agricole is the world's largest cooperative bank.

-

Banque Populaire Group

-

BNP Paribas in the world

-

La Nef, ethical banking

Evolution[edit]

In terms of imports and exports, the total volume of goods traded between Francophone countries grew at an average annual rate of around 9% between 1995 and 2008.[13]

The 2008 financial crisis resulted in a significant fall in trade volumes: -28% for exports and −21% for imports. However, these data reflect a greater resilience than other international economic areas over the same period;[13] indeed, the share of intra-French-speaking trade increased significantly over the period 2000–2015 and during the 2008 financial crisis, while the volume of global trade flows falls during the same period.

However, data show a recovery from 2010 onwards, with trade in the French-speaking world returning to pre-crisis levels from 2011.

According to trade data from 2015, exports of goods from countries in the French-speaking world (FSW) amounted to $1600 billion in 2015 and imports of goods to the FSW represented $1700 billion.

Despite divergent models on the evolution of the economic potential of French-speaking countries, existing projections (ODSEF, 2017; United Nations DASE, 2017[13]) agree that this demographic dynamic, driven mainly by sub-Saharan African countries, will continue throughout the 21st century.

References[edit]

- ^ https://www.francophonie.org/qui-sommes-nous-5

- ^ Carrère & Masood 2015, p. 1.

- ^ Jacques Melitz, « Language and foreign trade », European Economic Review, 52-4, 2008, p. 667-699.

- ^ L. Guiso, P. Sapienza, L. Zingales, « Cultural Biases in Economic Exchange », Quarterly Journal of Economics, 124, No. 3, 2009, p. 1095-1131 (en ligne).

- ^ a b https://www.oecd-forum.org/posts/quand-francophonie-rime-avec-economie

- ^ https://riafpi.org/

- ^ https://www.francophonie.org/la-francophonie-en-bref-754

- ^ https://theconversation.com/penser-lapres-la-reconstruction-plutot-que-la-reprise-137042

- ^ https://www.cpq.qc.ca/activites/rencontre-des-entrepreneurs-francophones-2023-presentiel/

- ^ https://www.francophonieinnovation.org/

- ^ https://patronats-francophones.org/

- ^ https://observatoire.francophonie.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/2018-Langue-francaise-Employabilite.pdf

- ^ a b c https://observatoire.francophonie.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/2018-espace-economique-francophone-M-Masood.pdf

See also[edit]

Bibliography[edit]

- Aymeric Chauprade (2000). L'espace économique francophone (in French). Paris: Ellipses. p. 128. ISBN 9782729846978..

- Hervé Cronel, « Que fait la Francophonie de l'économie ? », Hermès, La Revue, 40, 2004/3, p. 155-157 (en ligne).

- Céline Carrère, Maria Masood, Le poids économique de la langue française dans le monde, Clermont-Ferrand, Fondation pour les Études et Recherches sur le Développement International (FERDI), 2013.

- Carrère, Céline; Masood, Maria (2015). "Poids économique de la francophonie : impact via l'ouverture commerciale". Revue d'économie du développement (in French). 23 (2): 5–30. doi:10.3917/edd.292.0005. hdl:10419/269419. S2CID 162819711. Retrieved 28 April 2023..

- Boniface Bounoung Fouda (2021). Économie de la Francophonie (in French). Paris: Éditions du Panthéon. p. 152. ISBN 978-2-7547-5424-8..

Articles[edit]

External links[edit]

- Site officiel de la Délégation générale à l’Entreprenariat Rapide des Femmes et des Jeunes (DER/FJ), Sénégal

- Rapport : La Maîtrise de la langue française et l’emploi, Observatoire de la langue française de l’Organisation internationale de la francophonie, 2018.