Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie | |

|---|---|

Adichie in 2015 | |

| Born | 15 September 1977 Enugu, Enugu State, Nigeria |

| Occupation |

|

| Nationality | Nigerian; American |

| Alma mater | |

| Period | 2003–present |

| Notable works |

|

| Notable awards |

|

| Spouse |

Ivara Esege (m. 2009) |

| Children | 1 |

| Website | |

| www | |

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie (/ˌtʃɪməˈmɑːndə əŋˈɡoʊzi əˈdiːtʃi.eɪ/ ⓘ[a]; born 15 September 1977) is a Nigerian writer, novelist, poet, essayist, and playwright of postcolonial feminist literature. She is the author of the award-winning novels Purple Hibiscus (2003), Half of a Yellow Sun (2006) and Americanah (2013). Her other works include the book essays We Should All Be Feminists (2014); Dear Ijeawele, or A Feminist Manifesto in Fifteen Suggestions (2017); a memoir tribute to her father, Notes on Grief (2021); and a children's book, Mama's Sleeping Scarf (2023).

Born in Enugu, Enugu State, Adichie's childhood was influenced by postcolonial rule in Nigeria, including the aftermath of the Nigerian Civil War, which took the lives of both of her grandfathers and was a major theme of Purple Hibiscus and Half of a Yellow Sun. She excelled in academics and attended the University of Nigeria, where she initially studied medicine and pharmacy. She moved to the United States at 19, and studied communications and political science at Drexel University in Philadelphia before transferring to and graduating from Eastern Connecticut State University. Adichie later received a master's degree from Johns Hopkins University. She first published the poetry collection Decisions in 1997, which was followed by a play, For Love of Biafra, in 1998. In less than ten years, she published eight books: novels, book essays and collections, memoirs, and children's books. Adichie has cited Chinua Achebe—in whose house she lived while at the University of Nigeria—Buchi Emecheta, Enid Blyton and other authors as inspirations; her style juxtaposes Western influences and the Igbo language and culture.

Adichie's words on feminism were encapsulated in her 2009 TED talk "We Should All Be Feminists", which was adapted into a book of the same title in 2014. Most of her works delve the themes of immigration, racism, gender, marriage, motherhood and womanhood. In 2023, she made statements about LGBT rights in Nigeria in an interview with the British newspaper The Guardian, after which she was criticized for being transphobic.

Adichie has received several academic awards and fellowship grants. She was shortlisted for the Caine Prize for African Writing and has won the O. Henry Award, Hurston/Wright Legacy Award, and the PEN Pinter Prize, among others. She was awarded a MacArthur Fellowship in 2008 and inducted into the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 2017.

Early life, education, and family[edit]

Family and background[edit]

Ngozi Adichie, whose English name was Amanda,[3][4] was born on 15 September 1977, in Enugu, Nigeria, as the fifth out of six children, to Igbo parents, Grace (née Odigwe) and James Adichie.[5][6] She made up the name "Chimamanda" in the 1990s to keep her legal English name of "Amanda" and conform with Igbo Christian naming customs of the time,[b] which she revealed in an interview with the Nigerian television personality Ebuka Obi-Uchendu.[3][8] She was raised in Enugu, which lies in the southeastern part of Nigeria,[9] and had been the capital of the short-lived Republic of Biafra.[10]

Adichie's father was born in Abba, Anambra State, and studied mathematics at University College, Ibadan. After graduating in 1957, he worked for a few years and then in 1963, moved to Berkeley, California, to complete his PhD at the University of California. He returned to Nigeria and began working as a professor at the University of Nigeria, Nsukka, in 1966.[11] Her mother was born in Umunnachi, Anambra State.[5] James married Grace on 15 April 1963,[12] moving together to California.[13] While in the United States, the couple had two daughters.[12] Grace began her university studies in 1964, at Merritt College in Oakland, California, and then earned a degree in sociology and anthropology from the University of Nigeria.[5][14]

Shortly after the family returned to Nigeria, the Biafran War broke out and James started working for the Biafran government[13] at the Biafran Manpower Directorate.[15] The family lost almost everything including Adichie's maternal and paternal grandfathers during the 1966 anti-Igbo pogrom.[16] James wrote that both his brother, Michael Adichie, and brother-in-law, Cyprian Odigwe, fought for Biafra in the war.[15] James' father, David, and his father-in-law both died in refugee camps during the war. Obligated by custom which required the oldest child to bury the father,[13] when the war ended, James went to the refugee camp at Nteje to find his father's body and was told by officials that those who had died had been buried in a mass grave as they were unidentifiable. In a symbolic gesture, James took sand from the site of the mass grave to the cemetery in Abba to bury David with his family.[15][c]

Education and influences[edit]

After Biafra ceased to exist in 1970, James returned to the University of Nigeria in Nsukka[11][13] while Grace worked for the government at Enugu until 1973 when she became an administration officer at the university, later becoming the university's first female registrar.[5][14] The family stayed at the campus of the University of Nigeria, Nsukka, previously occupied by Nigerian writer Chinua Achebe.[18] When they moved in, the family included Ijeoma Rosemary, Uchenna "Uche", Chukwunweike "Chuks", Okechukwu "Okey", Ngozi, and Kenechukwu "Kene" and her father was then, the Deputy Vice-Chancellor of the university.[4][12] Adichie was Catholic and when she was young, she wished she could be a priest.[13] Her family's home parish was St. Paul's Parish in Abba.[15]

As a child, Adichie read only English-language stories,[13] especially by Enid Blyton. Adichie's juvenilia included stories with characters who were white and blue-eyed, modeled on British children she had read about.[13][15][19] At ten, she discovered African literature and began reading Things Fall Apart by Chinua Achebe,[18] The African Child by Camara Laye,[19] Ngũgĩ wa Thiong'o's Weep Not, Child and Joys of Motherhood by Buchi Emecheta.[15] Adichie began to study her father's stories about Biafra when she was thirteen. The war occurred before she was born, but in visits to Abba, she saw houses that were destroyed and some rusty bullets on the ground. She would later incorporate her memories and father's descriptions into her novels.[15] Adichie started her education in Igbo and English.[9] Although Igbo was not a popular subject, she continued taking courses in the language throughout high school.[13] She completed her secondary education at the University of Nigeria Campus Secondary School, Nsukka with top distinction in the West African Examinations Council (WAEC),[4] and academic prizes.[20] She was admitted to the University of Nigeria, and studied medicine and pharmacy for a year and half.[21] She was also the editor of The Compass, a student-run magazine in the university campus.[22]

Education abroad and early literary efforts[edit]

Adichie published Decisions, a collection of poems, in 1997 and then left for the United States.[19] At the age of 19, she moved from Nigeria to study communications at Drexel University in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.[20][22] She wrote For Love of Biafra, a play, in 1998, which was her initial exploration of the theme of war following the Nigerian Civil War.[19] These early works were written under the name Amanda N. Adichie.[3] Two years after moving to the United States, she transferred to Eastern Connecticut State University in Willimantic, Connecticut, where she lived with her sister Ijeoma, who was a medical doctor there.[9] In 2000, she published her short story "My Mother, the Crazy African",[23] which discusses the problems that arise when a person is facing two cultures that are complete opposites from each other.[24] After finishing her undergraduate degree, she continued her pattern of simultaneously studying and pursuing a writing career.[19] While a senior at Eastern Connecticut, she wrote articles for the university paper Campus Lantern.[22] She received her bachelor's degree summa cum laude with a major in political science and a minor in communications in 2001.[9][22] She earned a master's degree from Johns Hopkins University in creative writing in 2003,[22][25] and for the next two years was a Hodder Fellow at Princeton University where she taught introductory fiction.[19][20] She then began a course in African studies at Yale University, and completed a second master's degree in 2008.[9][19] Adichie received a MacArthur Fellowship that same year[26] plus other academic prizes, including the 2011–2012 Fellowship of the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study from Harvard University.[27] Adichie married Ivara Esege, a Nigerian doctor, in 2009,[13] and their daughter was born in 2016.[28] The family primarily lives in the United States because of Esege's medical practice, but they also maintain a home in Nigeria.[13]

Career[edit]

Writing[edit]

While studying in America, Adichie started researching and writing her first novel Purple Hibiscus. It was written during a period of homesickness and set in her childhood home of Nsukka, Nigeria.[15] The book explored post-colonial Nigeria during a military coup d'état and examined cultural conflicts between Christianity and Igbo traditions within the dynamics and generations of a family, touching on themes of class, gender, race, and violence.[29] She sent her manuscript to publishing houses and agents, who either rejected it, or requested that she change the setting from Africa to America, as it was more familiar to a broad range of readers. Eventually, she was emailed by Djana Pearson Morris, a literary agent working at Pearson Morris and Belt Literary Management, seeking the manuscript with lines saying, "I like this and I'm willing to take a risk on you."[15] Morris recognized that marketing would be challenging since Adichie was Black, and neither was she an African American nor Caribbean. Adichie, who was desperate to be published, sent her manuscript to the agent, who sent it to publishers untill it was accepted by Algonquin Books in 2003.[30] Algonquin focused on publishing debut novels and was not concerned with industry trends. Thus, they created support for the book by sending advance copies to booksellers, reviewers, and media houses. They also sent Adichie on a promotional tour[15] and the manuscript to Fourth Estate, who accepted the book for publication in the United Kingdom in 2004.[15] Adichie's hired the agent Sarah Chalfant of the Wylie Agency to represent her in the UK. The book was published by Kachifo Limited in Nigeria in 2004,[30] and subsequently translated into more than fourty languages.[15]

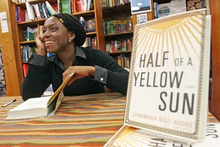

After her first book, Adichie began writing Half of a Yellow Sun. She worked on it for four years, researching extensively and studying her father's memories of the period and Buchi Emecheta's Destination Biafra.[31][32] It was first published by Anchor Books, a trademark of Alfred A. Knopf, who also released it later under its Vintage Canada label. It was also published in France as L'autre moitié du soleil in 2008, by Éditions Gallimard.[33] The novel expanded on the Biafran conflict weaving together a love story which included people from various regions and social classes of Nigeria, and how the war and encounters with refugees changed them.[13][32]

While completing her Hodder and MacArthur fellowships, Adichie published short stories in various magazines.[15] Twelve of these stories were collected into her third book, The Thing Around Your Neck, published by Knopf in 2009.[34] The stories focused on the experiences of Nigerian women, living at home or abroad, examining the tragedies, loneliness, and feelings of displacement, which result from their marriages, relocations, or violent events.[35]

The Thing Around Your Neck was a bridge between Africa and the African diaspora, which was also the theme of her fourth book, Americanah published in 2013.[15] It was the story of a young Nigerian woman and her male schoolmate, who had not studied the trans-Atlantic slave trade in school and had no understanding of the racism associated with being Black in the United States or class structures in the United Kingdom.[36][37] It exploded the myth of a "shared Black consciousness", as both of the characters, one who went to Britain and the other to America, experience a loss of their identity when they try to navigate their lives abroad.[37] In 2015, Adichie wrote a letter to a friend and posted it on Facebook in 2016. Comments on the post, convinced her to expand her ideas on how to raise a feminist daughter into a book,[38] Dear Ijeawele, or A Feminist Manifesto in Fifteen Suggestions which was published in 2017.[39] In 2020, she published "Zikora", a stand-alone short story about sexism and single motherhood,[40] and an essay "Notes on Grief" in The New Yorker, after her father's death. She expanded the essay into a book of the same name, which was published by the Fourth Estate the following year.[41][42]

Adichie spent a year and a half writing her first children's book, Mama's Sleeping Scarf, because she wanted her daughter's approval.[43] Although written in 2019, it was published in 2023 by HarperCollins under the pseudonym Nwa Grace James,[44] a dedication to her parents, as Nwa means "child of" in Igbo.[44][45] Illustrations for the book were made by Joelle Avelino, a Congolese-Angolan animator.[45] The book tells the story of the connections of generations through family interactions with a head scarf.[43]

Public speaking[edit]

Adichie has been praised for her writing and same way, for her speeches and lectures. While she claims to love Lagos and spends most of her time there, cited loving the culture, spirit, resilience and initiative of its people, which has improved her speaking life. Using people-watching as a strategy including staying on the traffic on a good mood and seeing other people, the hustlers, hawkers, lawyers and all other professions; those she will incorporate in her lectures. The different cultural diversity in Nigeria especially of her native Igbo culture, and Yoruba for instance said "there is a showiness to the Nigerian national character which cuts across our different cultural groups."[46] Adichie who's articulate and funny when speaking usually inserts personal anecdotes before generating a main point of her talk. Adichie has sharp words which she uses in addressing her audience especially when it comes to the code of silence known to have governed the Americans.[47] Whenever speaking, Adichie usually observe a long pause especially when the audience reacts to something hilarious or actable. It is basically to give them time either to applaud or she'll laugh along.[48] In 2009, Adichie delivered a TED talk entitled "The Danger of a Single Story", which as of 2024, is one of the top twenty most-viewed TED talks of all time.[49] In the talk, Adichie expressed her concern for the under-representation of various cultures. American critic and author Erica Wagner called it an "accessible essay on how we might see the world through another's eyes."[50] In concluding the talk, Adichie noted the importance of hearing various stories of communities and advocated for a greater understanding of different stories matters, since the world has many cultures too. Since 2009, she had revisited the topic when speaking to audience such as at the Hilton Humanitarian Symposium of the Conrad N. Hilton Foundation in 2019.[51]

Adichie, in 2013 accepted an invitation to speak in London for a TEDx talk entitled "We Should All Be Feminists",[52] at TEDxEuston, a series of talks focusing on African affairs because it was organised by Chuks Adichie, her brother who works in the technology and information development department and that she wanted to aid him.[50] In the talk, Adichie addressed her view of African feminism towards class, race, gender, and sexuality.[50] She said particularly to the gender issue, how she is becoming less interested in the way the West sees continent Africa, and more interested in how Africa sees itself.{{|Dabiri|2017}}

Parts of Adichie's TEDx talk were sampled in the song "Flawless" by singer Beyoncé on 13 December 2013. When asked in an NPR interview about that, Adichie responded that anything that gets young people talking about feminism is a very good thing.[53] She later qualified the statement in an interview with the Dutch newspaper De Volkskrant: "Another thing I hated was that I read everywhere: now people finally know her, thanks to Beyoncé, or: she must be very grateful. I found that disappointing. I thought: I am a writer and I have been for some time and I refuse to perform in this charade that is now apparently expected of me: 'Thanks to Beyoncé, my life will never be the same again.' That's why I didn't speak about it much."[54] Adichie has been outspoken against critics who question the singer's credentials as a feminist and has said: "Whoever says they're feminist is bloody feminist."[55]

On 15 March 2012, Adichie delivered the Commonwealth Lecture 2012 at the Guildhall, London, addressing the theme "Connecting Cultures" and explaining: "Realistic fiction is not merely the recording of the real, as it were, it is more than that, it seeks to infuse the real with meaning. As events unfold, we do not always know what they mean. But in telling the story of what happened, meaning emerges and we are able to make connections with emotive significance."[56][57] On 30 November 2022, Adichie delivered the first of the BBC's 2022 Reith Lectures, inspired by Franklin D. Roosevelt's "Four Freedoms" speech.[58][59]

Adichie who was the co-curator of the PEN World Voices, along the director Laszlo Jakab Orsos, sat on a front-row seat for the debates about Charlie Hebdo who was said had overshadowed the festival events. Adichie, in her Arthur Miller Freedom to Write lecture, which marked the closing of the festival told the audience that "there is a general tendency in the United States to define problems of censorship as essentially foreign problems." In contrast between the Nigerian and American hospitals, Adichie argued that American citizens seem to be "comfortable", thus bringing a "dangerous silencing" amidst the United States public conversation. Adichie’s address sparked a feeling of sadness following the release of her father, who was kidnapped in Nigeria. Though wasn't mentioned in the lecture, she called Nigerians people who considers "pain" for living.[47]

Themes and style[edit]

Themes[edit]

Adichie, in a 2011 conversation with Kenyan writer Binyavanga Wainaina, stated that the overriding theme of her works was love.[60] Using the feminist argument "The personal is political", love in her works typically is expressed through cultural identity, personal identity, and the human condition, and how these are impacted by social and political conflict.[61] She frequently explores the intersections of class, culture, gender, (post-)imperialism, power, race, and religion.[62] Struggle is a predominant theme throughout African literature,[63] and Adichie's works follow in that tradition by examining families, communities, and relationships.[64] Her explorations go beyond political strife and the struggle for rights, and typically examine what it is to be human.[65] Many of her works deal with how the characters reconcile themselves with the trauma in their lives[66] and how they move from being silenced and voiceless to self-empowered and able to tell their own stories.[67]

Adichie's works, beginning with Purple Hibiscus, generally examine cultural identity.[68] Igbo identity is typically at the forefront of her works, which celebrate Igbo language and culture, and African patriotism, in general.[69] Her writing is an intentional dialogue with the West, intent on reclaiming African dignity and humanity.[60] A recurring theme in Adichie's works is the Biafran War. The civil war was a "defining moment" in the post-colonial history of Nigeria and examining the conflict dramatises the way that the identity of the country was shaped. Her major work on the war, Half of a Yellow Sun highlights how policies, corruption, religious dogmatism, and strife played into the expulsion of the Igbo population and then forced their reintegration into the nation.[70][71] Both actions had consequences, and Adichie presents the war as an unhealed wound, because of the reluctance for political leaders to address the issues that sparked it.[72]

The University of Nigeria, Nsukka, reappears in Adichie's novels to illustrate the transformative nature of education in developing political consciousness, as well as symbolises the stimulation of Pan-African consciousness and a desire for independence in Half of a Yellow Sun. It appeared in both Purple Hibisus and Americanah as the site of resistance to authoritarian rule through civil disobedience and dissent by students.[73] The university is also where one learns the colonial accounts of history and develops the means to contest its distortions through indigenous knowledge,[74] by recognising that colonial literature tells only part of the story and minimises African contributions.[75] Adichie illustrates this in Half of a Yellow Sun, when mathematics instructor Odenigbo, explains to his houseboy Ugwu, that he will learn in school that the Niger River was discovered by a white man named Mungo Park, although the indigenous people had fished the river for generations. But, Odenigbo cautions Ugwu that even though the story of Park's discovery is false, he must use the wrong answer or he will fail his exam.[74]

Adichie's diasporic works consistently examine themes of belonging, adaptation, and discrimination.[76] In her diasporic fiction, this is often shown as an obsession to assimilate and is demonstrated by characters changing their names, [77] a common theme to most of Adiche's short fiction, which is used to point out hypocrisy.[78] By using the theme of immigration, she is able to develop dialogue on how her characters' perceptions and identity are changed by living abroad and encountering different cultural norms.[79] Initially alienated by the customs and traditions of a new place, the characters, such as Ifemelu in Americanah, eventually discover ways to connect with communities in the location.[80] Ifemelu's connections are made through self-exploration, which rather than leading to assimilation of her new culture, lead her to a heightened awareness of being part of the African diaspora,[81] and adoption of a dual perspective which reshapes and transforms her sense of self.[82] Awareness of Blackness as part of identity, initially a foreign concept to Africans upon arriving in the United States,[83] is shown not only in her diasporic works, but also Adichie's feminist tract, Dear Ijeawele or A Feminist Manifesto in Fifteen Suggestions. In it, she evaluates themes of identity which recur in Purple Hibiscus, Half of a Yellow Sun, and The Thing Around Your Neck such as stereotypical perceptions of Black women's physical appearance, their hair, and their objectification.[84] Dear Ijeawele stresses the political importance of using African names,[85] rejection of colorism,[86] exercising freedom of expression in how they wear their hair (including rejecting patronising curiosity about it),[87] and avoiding commodification, such as marriageability tests which reduce a woman's worth to that of a prize, seeing only her value as a man's wife.[88] Her women characters repeatedly assertively resist being defined by stereotypes and embody a quest for women's empowerment.[89]

Adichie's works often deal with inter-generational explorations of family units which allow her to examine differing experiences of oppression and liberation. In both Purple Hibiscus and the "The Headstrong Historian", one of the stories included in The Thing Around Your Neck, Adichie examined these themes using the family as a miniature representation of violence for the nation.[90] Female sexuality, both within patriarchal marriage relationships and outside of marriage are frequent themes, which Adichie typically uses to explore romantic complexities and boundaries, although her works do not explore homosexuality. She discusses such things as marital affairs in stories like "Transition to Glory", taboo topics like romantic feelings for clergy in Purple Hibiscus, and seduction of a friend's boyfriend in "Light Skin". Miscarriage,[91] motherhood, and the struggles of womanhood are recurring themes in Adichie's works, and are often examined in relation to Christianity, patriarchy, and social expectation.[92][93][94] For example, in the short story "Zikora", she deals with the interlocking biological, cultural, and political aspects of becoming a mother and expectations placed upon women.[93] The story examines the failure of contraception and an unexpected pregnancy, abandonment by her partner, single motherhood, social pressure, and Zikora's identity crisis, and the various emotions she experiences about becoming a mother.[95]

Adichie's works show a deep interest in humanity and the complexities of the human condition. She repeats themes like forgiveness and betrayal in works such as Half of a Yellow Sun, when Olanna forgives her lover's infidelity or Ifemelu's decision to separate from her boyfriend in Americanah.[61] Her examination of war shines a light on how both sides of any conflict commit atrocities and neither side is blameless for the unfolding violence. Her narrative demonstrates that knowledge and understanding of diverse classes and ethnic groups is necessary to create harmonious multi-ethnic communities.[71] Other forms of violence, like sexual abuse, rape, domestic abuse, and rage are repeated themes in Purple Hibiscus, Half of a Yellow Sun, and the stories collected in Things Fall Apart.[71][64] Each of these themes are used to symbolize the universality of power or the misuse of power and its impact on and manifestation in society.[96]

Style[edit]

As a Nigerian, who was educated bilingually, Adichie consciously uses both Igbo and English in her works.[97] Rather than writing in English, she mixes language and speech patterns so that her works speak to a global audience.[69] Igbo phrases are typically shown in italics and followed by an English translation.[98] She uses metaphors, language, and food to trigger sensory experiences in the reader.[76] For example, in Purple Hibiscus, the arrival of a king to challenge colonial and religious leaders symbolizes Palm Sunday.[99] In the same book, she uses language references from Chinua Achebe's Things Fall Apart to stimulate the memories of his works to her readers.[100] Similarly, the name of Kambili, a character in Purple Hibiscus, evokes "i biri ka m biri" ("Live and Let Live"), the title of a song by Igbo musician Oliver De Coque.[101] To describe pre- and post-war conditions, in Half of a Yellow Sun, Adichie begins with a character opening the refrigerator and describes how as the cool air embraced him, he saw oranges, beer, and a "roasted shimmering chicken". This contrasts to the later period in the novel when people are dying of starvation, in which her characters are forced to eat powdered eggs and lizards.[102] She also repeatedly references real places and historic figures, to draw readers into the stories.[103] Adichie deliberately demonstrates the interconnections between cultures by alluding to historic events and well-known personality types,[104] demonstrating conflicts and relationships through interactions between characters.[105] By utilizing lived realities, intimate details, and drawing upon the senses, she compels the reader to look at the meaning of events and relationships.[106]

In developing characters, Adichie often exaggerates attitudes to contrast differences between traditional culture and westernization.[68] Her stories often point out cultural failures, particularly those which leave her characters in a limbo between bad options that have negative impacts.[107] At times, she creates a character as an oversimplified archetype of a particular aspect of cultural behavior to create a foil for a more complex character.[77] According to writer Izuu Nwankwọ, Adichie's choice of character names is a conscious selection used to identify various ethnicities.[108] Most of her characters are given easily-recognizable common names related to the intended ethnicity, such as using Mohammed for a Muslim character.[109] For Igbo characters, she invents names to convey to the reader the aesthetic and political connotations of Igbo naming traditions, which are assigned to depict character traits, personality, and social connections.[110] For example, in Half of a Yellow Sun, the character Ọlanna's name meaning is given in the text as "God's Gold", but Nwankwọ points out that "ọla" means precious and "nna" means father (which can be understood as either God the father or a parent).[108] By shunning popular Igbo names, Adichie intentionally imbues her characters with multi-ethnic, gender plural, and global personas.[111] She typically does not use English names for African characters, and when she does, it is a device to represent negative traits or behaviors.[112]

In contrast to western separation of history into objective and scientific facts and literature into creative imaginings of art, Igbo-Nigerian novels draw on figures from Igbo oral traditions to present truths in the style of historical fiction.[113] The genre utilises the custom of African societies to produce knowledge by revising and owning oral narratives in retelling stories to enable interaction between the storyteller and the community.[114] Stories became communal productions which allowed the past and future the flexibility to encompass more than one truth, by incorporating both informative and creative elements.[115] When the shift was made from oral retelling to the development of writing novels, African novelists used these traditions to contest western distortions of African cultures.[116] Following in these traditions, Adichie's works typically have ambiguous endings, indicating that cross-cultural experiences are in a continuous state of change.[117] As Belgian Africanist Daria Tunca describes,[118] refusal to provide closure "skillfully avoids reproducing" the questionable behaviors which Adichie has highlighted.[117] Adichie breaks with tradition as well, in that in earlier African literature, women writers were often absent from the Nigerian literary canon,[119] and female characters were often overlooked or became background material for male characters who were engaged in the socio-political and economic life of the community.[120] Her style often focuses on strong women and adds gender perspectives to topics previously explored by other authors, such as colonialism, religion, and power relationships.[121][92]

Adichie evaluates major social issues by deconstructing them to explore various interpretations. As an example, she often separates characters into social classes or traditional hierarchies to illustrate social ambiguities, attitudes, contradictions, power structures, restrictions, and roles.[122][123] Her written works acknowledge that men and women experience history differently.[124] By using narratives from characters of different segments of society, she reiterates her message in her TED talk, "The Danger of a Single Story", that there is no single truth about the past.[125] Scholar Silvana Carotenuto argues that by drawing on themes which have had global impacts on shared history, Adichie is compelling her readers to recognise their own responsibility for everyone else and the injustice which exists in the world.[96] According to Nigerian literary scholar and researcher Stanley Ordu, building unity and finding wholeness by removing oppression from all humans to effect change is a facet of African womanism.[126] Ordu classifies Adichie's feminism as womanist because her analysis of patriarchal systems goes beyond sexist treatment of women and anti-male biases, looking instead at socio-economic, political, and racial struggles women face to survive and cooperate with men.[127] For example, in Purple Hibiscus the character Auntie Ifeoma embodies a womanist world-view through coaching and encouraging all family members to work as a team and with consensus, so that each person's talents are utilized to their highest potential.[128] By focusing on the group as a collective unit, she promotes not only empowerment, but a focus on each team member's well-being.[129]

Critical reception[edit]

Luke Ndidi Okolo, a lecture a Nnamdi Azikiwe University said, "Adichie's novel treats clear and lofty subjects and themes. But the subjects and themes, however, are not new to African novels. The remarkable difference of excellence in Chimamanda Adichie's "Purple Hibiscus" is the stylistic variation – her choice of linguistic and literary features, and the pattern of application of the features in such a wondrous juxtaposition of characters' reasoning and thought."[130] Adichie's work has garnered significant critical acclaim and numerous awards.[131][132] Book critics such as Daria Tunca wrote that Adichie's work is considerably relevant and stated that she was a major voice in the Third Generation of Nigerian writers,[117] while Izuu Nwankwọ called her invented Igbo naming scheme as an "artform", which she has perfected in her works.[111] He lauded her ability to insert Igbo language and meaning into an English language text without disrupting the flow or distorting the storyline.[133] Scholars such as Ernest Emenyonu, one of the most prominent scholars of Igbo literature,[134] said that Adichie was "the leading and most engaging voice of her era" and he called her "Africa's preeminent storyteller".[135] Toyin Falola, a professor of history hailed her along other writers, as "intellectual heroes".[136] Her memoir, Notes On Grief was positively praised by Kirkus Reviews as "an elegant, moving contribution to the literature of death and dying."[137] Leslie Gray Streeter of The Independent said that Adichie's thoughts on grief "puts a welcome, authentic voice to this most universal of emotions, which is also one of the most universally avoided."[138] She has been widely recognised as "the literary daughter of Chinua Achebe."[139] Jane Shilling of the Daily Telegraph called her "one who makes storytelling seem as easy as birdsong".[140]

In 2002, Adichie was shortlisted for the Caine Prize for African Writing for her story, "You in America."[4][141] She also won the BBC World Service Short Story Competition for "That Harmattan Morning", while her short story "The American Embassy" won the 2003 O. Henry Award and the David T. Wong International Short Story Prize from PEN International.[142] Her book, Purple Hibiscus was well received with positive reviews from book critics.[15][30] the book sold well and was awarded the Commonwealth Writers' Prize for the Best Book (2005), Hurston-Wright Legacy Award, and shortlisted for the Orange Prize for Fiction (2004),[142][30] Half of a Yellow Sun garnered acclaim including winning the Orange Prize for Fiction in 2007,[143] and the Anisfield-Wolf Book Award.[142] Half of a Yellow Sun was later adapted into a film of the same title directed by Biyi Bandele in 2013.[144] Her book story collection, The Thing Around Your Neck was the runner-up to the Dayton Literary Peace Prize for 2010.[145] One story from the book, "Ceiling" was included in The Best American Short Stories 2011.[146] Americanah was listed among the "10 Best Books of 2013" by The New York Times,[142][147] and won the National Book Critics Circle Award (2014),[15][148][149] and the One City One Book (2017).[150]

Adichie was a finalist of the Andrew Carnegie Medal for Excellence in Fiction (2014).[151] She won the Barnard Medal of Distinction (2016),[152] and the W. E. B. Du Bois Medal (2022), the highest honour from Harvard University.[153] She was listed in The New Yorkers "20 Under 40" authors in 2010, and the Africa39 under 40 authors during the Hay Festival in 2014,[142] She was also among the "100 Most Influential People" by Time magazine in 2015,[154] and The Africa Report's list of the "100 Most Influential Africans" in 2019.[155]

In 2017, Adichie was elected as one of 228 new members to be inducted into the 237th class of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, one of the highest honours for intellectuals in the United States as well as the second Nigerian to be given the honour after Wole Soyinka.[156] As of March 2022, Adichie had received 16 honourary degrees from universities[157] including Johns Hopkins University (2016), Haverford College (2017), the University of Edinburgh (2017),[142] American University (10 May 2018), Georgetown University (18 May 2018), Yale University (20 May 2018), Rhode Island School of Design (June 2019),[158] Eastern Connecticut State University, Williams College, Duke University, Amherst College (2018), Bowdoin College, SOAS University of London, Northwestern University, and the Catholic University of Louvain (2022).[159] President of Nigeria Muhammadu Buhari selected her to be honoured as a recipient of the Order of the Federal Republic in 2022,[160] but Adichie rejected the national distinction.[161]

Views and controversy[edit]

Feminist fashion[edit]

Adichie, in a 2014 article written for Elle.com, describes herself in relation to fashion as one who gets less occupied with clothing and hair until she entered the West and discovered the difficult relationship between presumed intelligence and dressing up. She wrote much on Western culture and how she sees women desiring seriousness ends up being judged of their dressing. She admitted that it is better for women writers especially not to dress well but if Incase, should do as if its normal. Adichie's work has deliberately reflected her love for fashion, while still standing that fashion and its elements beauty and style shouldn't be gendered. For her, it contradicts with social justice, racism, and class structuring.[162]

On May 8, 2017, Adichie through her Facebook page created awareness for her "Wear Nigerian" campaign following the termed "disastrous economic policies" which lead to decline in market value of the Nigerian naira and trouble for the middle class (usually seen in her literally works),[163] and to the launch of the "Buy Nigerian to Grow the Naira" campaign endorsed by the Government of Nigeria. Following her fashion life, the campaign was to patronise and publicise Nigerian fashion brands as well as local designers by wearing their products in public. The clothes which would be worn will be documented in a new Instagram page to be managed by her nieces Chisom and Amaka.[164]

Adichie's work, referenced by Maria Grazia Chiuri, the first female creative director of American fashion company Dior in her debut collection advocated for fashion and makeup and how they are mutually not exclusive from feminism. She appeared in the front-row of the company's spring runway show during the Paris Fashion Week, as a honoured guest where T-shirts were printed with writings, "We Should All be Feminists."[165] Adichie saying that the politics of the company had never been her interest despite being a fashion company and her, loving fashion emerged from the appointment of Grazia as the first female ever, and her question becomes why the company had lacked female creative directors over the years. For Adichie, it is a shame for women lacking to defend their love of fashion and beauty.[166] In a discussion with the former Chancellor of Germany Angela Merkel at Düsseldorfer Schauspielhaus, Adichie who wore a printed attire which was made from her mother's wrapper traditionally tied around the waist, spoke on politics and how it affects feminism and fashion. Alongside journalists Miriam Meckel and Léa Steinacker, Adichie argues that the world has survived many political disorder while she believed still, there is hope. She sees fashion as a media for promoting talents especially in Nigeria.[167]

Adichie was included in the 2016 Vanity Fair's International Best-Dressed Lists, while citing Michelle Obama as her styling idol.[168][169] Adichie's TED talk, "We Should All Be Feminists" which was part of her view of femininity and fashion feminism recognized by singer Beyoncé, became the face of No.7, a makeup brand division of British drugstore retailer Boots.[170] Her view of feminism seems to be different to the 21st-century world of fashion, that in her book Dear Ijeawele, or A Feminist Manifesto in Fifteen Suggestions, she argued that feminine associated acts like fashion and makeup remains a culture of sexism.[169] In 2019, she was selected as one of 15 women to appear on the cover of the British Vogue, guest-edited by Meghan, Duchess of Sussex.[171]

Religion[edit]

Although Adichie was raised as a Catholic, she considers her views, especially those on feminism, to sometimes conflict with her religion. In a 2017 event at Georgetown University, she stated that differences in ideology between Catholic and Church Missionary Society leaders caused divisions in Nigerian society during her childhood and she left the church around the time of the inauguration of Pope Benedict XVI.[172] As sectarian tensions in Nigeria arose between Christians and Muslims in 2012, she urged leaders to preach messages of peace and togetherness.[173] Adichie stated that her relationship to Catholicism is complicated because she identifies culturally as Catholic, but feels that the focus of the church on money and guilt are not in-line with her values.[174] She acknowledged that the birth of her daughter and election of Pope Francis drew her back to the Catholic faith and a decision to raise her child as Catholic.[172] But by 2021, Adichie stated that she was a nominal Catholic and only attended mass when she could find a progressive community focused on uplifting humanity. She clarified that "I think of myself as agnostic and questioning".[174]

LGBT rights[edit]

Adichie is an activist and supporter of LGBT rights in Africa. B. Camminga called her "a vocal campaigner for LGBT rights in Nigeria",[175] and Emily Crockett said she is "an LGBTQ-rights advocate in Nigeria".[176] Adichie has questioned whether consensual homosexual conduct between adults rises to the standard of a crime, as crime requires a victim and harm to society. When Nigeria passed an anti-homosexuality bill in 2014, she was among the Nigerian writers who objected to the law, calling it unconstitutional, unjust, and "a strange priority to a country with so many real problems". She stated that adults expressing affection for each other did not cause harm to society, but that the law would "lead to crimes of violence".[177] Adichie was close friends with Kenyan writer Binyavanga Wainaina, who she credited with demystifying and humanising homosexuality when he publicly came out in 2014.[178][179] Writer Bernard Dayo said that Adichie's eulogy to Wainaina when he died in 2019, perfectly captured the spirit of the "bold LGBTQ activist [of] the African literary world where homosexuality is still treated as a fringe concept."[180]

Since 2017, Adichie has been repeatedly accused of transphobia, initially for saying that "my feeling is trans women are trans women" in an interview aired on Channel 4 in Britain.[181][176] She apologised, and acknowledged that trans-women need support and that they have experienced severe oppression, but she also stated that the differences between transgender women and other women's experiences are different and one could acknowledge those differences without invalidating or diminishing either's lived experience.[176] After the apology, Adichie attempted to clarify her statement,[176] by stressing that girls are socialised in ways that damage their self-worth, which have lasting impact throughout their lives, whereas boys benefit from male privilege that give them life advantages, before transitioning.[176][182] Some accepted her apology,[176] and others rejected it as a trans-exclusionary radical feminist view that biological sex determines gender.[182]

Selected works[edit]

Books[edit]

- ——— (1997). Decisions (poetry). London: Minerva Press. ISBN 978-1-86106-422-6.

- ——— (1998). For Love of Biafra (play). Ibadan: Spectrum Books. ISBN 978-978-029-032-0.

- ——— (2003). Purple Hibiscus (novel). London: 4th Estate. ISBN 978-0-00-718988-5

- ——— (2006). Half of a Yellow Sun (novel). London: 4th Estate. ISBN 978-0-00-720028-3.

- ——— (2009). The Thing Around Your Neck (short-story collection). London: 4th Estate. ISBN 978-0-00-730621-3.

- ——— (2013). Americanah (novel). New York City: Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 978-0-307-27108-2.

- ——— (2014). "We Should All Be Feminists" (essay). London: 4th Estate. ISBN 978-0-00-811527-2. (excerpt in New Daughters of Africa; edited by Margaret Busby, 2019)[183]

- ——— (2017). "Dear Ijeawele, or A Feminist Manifesto in Fifteen Suggestions" (essay). London: 4th Estate. ISBN 978-0-00-827570-9.

- ——— (2021). Notes on Grief (memoir/personal essay). London: 4th Estate. ISBN 978-0-593-32080-8.

- ——— (2023). Mama's Sleeping Scarf (children picture book). London/New York: HarperCollins Children's Books/Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 978-0-00-855007-3.

Short fictions[edit]

- ——— (4 June 2006). "Sierra Leone, 1997". The New Yorker. New York City, New York: Condé Nast.

- ——— (22 January 2007). "Cell One". The New Yorker. New York City, New York: Condé Nast.

- ——— (16 June 2008). "The Headstrong Historian". The New Yorker. New York City, New York: Condé Nast.

- ——— (28 December 2008). "A Private Experience". The Guardian. London, UK.

- ——— (1 February 2010). "Quality Street". Guernica. New York City, New York: Guernica Inc.

- ——— (20 September 2010). "Birdsong". The New Yorker. New York City, New York: Condé Nast.

- ——— (18 March 2013). "Checking Out". The New Yorker. Vol. 89, no. 5. New York City, New York: Condé Nast. pp. 66–73.

- ——— (13 April 2015). "Apollo". The New Yorker. Vol. 91, no. 8. New York City, New York: Condé Nast. pp. 64–69.

- ——— (3 July 2016). "'The Arrangements': A Work of Short Fiction". The New York Times Book Review. New York City, New York.

- ——— (October 2020). "Zikora: A Short Story". Amazon Original Stories. Asin: BO8K942N84.

Videos[edit]

- ——— (6 October 2009). The Danger of a Single Story (video). Oxford, UK: TED talks. OCLC 819784502. Transcript by James Clear.

- ——— (December 2012). We Should All Be Feminists (video). London, UK: TEDxEuston. OCLC 1037277746. We Should All Be Feminists by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie Full Transcript.

- ——— (March 2012). To Instruct and Delight: A Case for Realist Literature (video). London, UK: Commonwealth Foundation. To Instruct and Delight transcript (PDF).

- ——— (2015). Wellesley College Commencement Address (video). Wellesley, Massachusetts: Wellesley College.

- ——— (2017). Williams College Commencement Address (video). Williamstown, Massachusetts: Williams College. Commencement Address.

- ——— (2019). The Inaugural Gabriel García Márquez Lecture: Para reivindicar a la mujer negra / To Vindicate Black Women (video). Cartagena, Colombia: The Hay Festival. Transcript summary in Spanish.

- ——— (2022). Freedom of Speech (video). London, UK: Reith Lectures.

See also[edit]

References[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^ CHI-mə-MAHN-də əng-GOH-zee ə-DEE-chee-ay Adichie's name has been pronounced a variety of ways in English. This transcription attempts to best approximate the Igbo pronunciation for English-speaking readers.

- ^ In translation, the Igbo name "Chimamanda" means "my spirit is unbreakable" or "My God cannot fail".[7]

- ^ Adichie's father died of kidney failure in 2020, during the COVID-19 pandemic,[17] and her mother died in 2021.[5]

Citations[edit]

- ^ Brockes 2017.

- ^ Adichie 2013.

- ^ a b c Nwankwọ 2023.

- ^ a b c d Anya 2005.

- ^ a b c d e This Day 2021.

- ^ Luebering 2024.

- ^ Tunca 2010, p. 300.

- ^ Akinyoade 2021.

- ^ a b c d e Mullane 2014.

- ^ Mwakikagile 2001, p. 27.

- ^ a b The Sun 2020.

- ^ a b c The Sun 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k MacFarquhar 2018.

- ^ a b Martin 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Obi-Young 2021.

- ^ Adichie 2006.

- ^ Broom 2021.

- ^ a b Murray 2007.

- ^ a b c d e f g Tunca 2011.

- ^ a b c Business Day 2016.

- ^ Agbo 2018.

- ^ a b c d e Braimah 2018.

- ^ Adichie 2000.

- ^ Tunca 2010, pp. 297–298.

- ^ Krieger 2015.

- ^ Irvine 2008.

- ^ Okachie 2011.

- ^ Chutel 2016.

- ^ Dube 2019, pp. 222, 227.

- ^ a b c d Obi-Young 2018.

- ^ Busby 2017.

- ^ a b McGrath 2006.

- ^ Madueke 2019, p. 49.

- ^ Kirkus Reviews 2009.

- ^ Forna 2009.

- ^ Fresh Air 2013.

- ^ a b Day 2013.

- ^ Greenberg 2017.

- ^ Bhuta 2018, p. 319.

- ^ Law 2020.

- ^ Flood 2021.

- ^ Lozada 2021.

- ^ a b Krug 2003.

- ^ a b Obi-Young 2022.

- ^ a b Ibeh 2022.

- ^ Calkin 2013.

- ^ a b Lee 2015.

- ^ Anasuya 2015.

- ^ TED 2022.

- ^ a b c Nast & Wagner 2015.

- ^ Rios 2019.

- ^ Behrmann 2017, pp. 316, 316.

- ^ NPR 2014.

- ^ Kiene, Aimée (7 August 2016). "Ngozi Adichie: Beyoncé's Feminism Isn't My Feminism". De Volkskrant. The Netherlands. Archived from the original on 20 November 2020.

- ^ Danielle, Britni (20 March 2014). "Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie Defends Beyoncé: 'Whoever Says They're Feminist is Bloody Feminist'". Clutch Magazine. UK. Archived from the original on 22 April 2014.

- ^ "Prize winning author Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie to speak at Commonwealth Lecture". thecommonwealth.org. The Commonwealth. 10 February 2012. Archived from the original on 30 September 2016. Retrieved 16 January 2017.

- ^ "Commonwealth Lecture 2012: Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, 'Reading realist literature is to search for humanity'". Commonwealth Foundation. London, UK. 28 May 2012. Archived from the original on 18 October 2012.

- ^ "Four speakers to deliver the BBC Radio 4 Reith Lectures 2022 | Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, Lord Rowan Williams, Darren McGarvey and Dr Fiona Hill to deliver lectures inspired by Franklin D Roosevelt's Four Freedoms speech". Media Centre. BBC. 30 September 2022. Archived from the original on 23 March 2024. Retrieved 2 December 2022.

- ^ "Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie delivers BBC Reith Lecture on Freedom of Speech". Vanguard. Nigeria. 1 December 2022. Archived from the original on 1 December 2022. Retrieved 2 December 2022.

- ^ a b Tunca 2018, p. 111.

- ^ a b Tunca 2018, p. 112.

- ^ Dube 2019, p. 222.

- ^ Hewett 2005, p. 76.

- ^ a b Hewett 2005, pp. 79–80.

- ^ Hewett 2005, p. 90.

- ^ Hewett 2005, p. 84.

- ^ Hewett 2005, pp. 85–86.

- ^ a b Tunca 2010, p. 295.

- ^ a b Ishaya & Gunn 2022, p. 74.

- ^ Hewett 2005, p. 79.

- ^ a b c Abba 2021, p. 5.

- ^ Abba 2021, p. 3.

- ^ Egbunike 2017, p. 20.

- ^ a b Egbunike 2017, p. 21.

- ^ Egbunike 2017, p. 22.

- ^ a b Tunca 2010, p. 296.

- ^ a b Tunca 2010, p. 297.

- ^ Tunca 2010, pp. 299–300.

- ^ Bragg 2017, p. 130.

- ^ Bragg 2017, p. 129.

- ^ Bragg 2017, pp. 129–131.

- ^ Bragg 2017, p. 136.

- ^ Akyeampong 2021, pp. 90–91.

- ^ Sebola 2022, pp. 1–2.

- ^ Sebola 2022, pp. 2–3.

- ^ Sebola 2022, pp. 3–4.

- ^ Sebola 2022, p. 5.

- ^ Sebola 2022, p. 6.

- ^ Sebola 2022, pp. 6–7.

- ^ Egbunike 2017, p. 26.

- ^ Hewett 2005, p. 81.

- ^ a b Hewett 2005, p. 80.

- ^ a b Roifah 2021, p. 179.

- ^ Daniels 2022, p. 54.

- ^ Roifah 2021, pp. 182–183.

- ^ a b Carotenuto 2017, p. 173.

- ^ Ishaya & Gunn 2022, pp. 73–74.

- ^ Ishaya & Gunn 2022, p. 78.

- ^ Dube 2019, p. 225.

- ^ Dube 2019, pp. 226–227.

- ^ Nwankwọ 2023, p. 7.

- ^ Mbah 2015, p. 352.

- ^ Ejikeme 2017, p. 312.

- ^ Nwankwọ 2023, p. 11.

- ^ Mbah 2015, p. 347.

- ^ Ishaya & Gunn 2022, p. 76.

- ^ Tunca 2010, p. 305.

- ^ a b Nwankwọ 2023, p. 5.

- ^ Nwankwọ 2023, pp. 5–6.

- ^ Nwankwọ 2023, pp. 2–3.

- ^ a b Nwankwọ 2023, p. 3.

- ^ Nwankwọ 2023, p. 4.

- ^ Egbunike 2017, pp. 18–19.

- ^ Egbunike 2017, p. 17.

- ^ Egbunike 2017, pp. 17–18.

- ^ Egbunike 2017, p. 18.

- ^ a b c Tunca 2010, p. 306.

- ^ Zabus 2015, p. 234.

- ^ Hewett 2005, p. 77.

- ^ Vanzanten 2015, pp. 87–88.

- ^ Vanzanten 2015, p. 90.

- ^ Ndula 2017, pp. 32.

- ^ Sharobeem 2015, p. 26.

- ^ Ejikeme 2017, p. 308.

- ^ Ejikeme 2017, p. 309.

- ^ Ordu 2021, pp. 63–64.

- ^ Ordu 2021, pp. 61–63.

- ^ Ordu 2021, p. 70.

- ^ Ordu 2021, p. 72.

- ^ Okolo 2016, p. 12.

- ^ Ishaya & Gunn 2022, pp. 75.

- ^ Hewett 2005, p. 75.

- ^ Nwankwọ 2023, p. 8.

- ^ Igwe 2017, p. 7.

- ^ Abba 2021, p. 2.

- ^ Olaopa 2022.

- ^ Kirkus Reviews 2021.

- ^ Streeter 2021.

- ^ Tunca 2018, p. 109.

- ^ Shilling 2009.

- ^ Caine Prize 2009.

- ^ a b c d e f Leadership 2018.

- ^ Majendie 2007.

- ^ Felperin 2013.

- ^ Richardson 2011, pp. 114–115.

- ^ Sam-Duru 2014.

- ^ The New York Times 2013.

- ^ National Book Critics 2014.

- ^ Flood 2014.

- ^ Weller 2017.

- ^ Italie 2014.

- ^ Jaschik 2016.

- ^ Edeme 2022.

- ^ Jones 2015.

- ^ Ventures Africa 2019.

- ^ Ayo-Aderele 2017.

- ^ Guardian Nigeria 2022.

- ^ Aneasoronye 2019.

- ^ Jordan 2022.

- ^ Ufuoma 2022.

- ^ Olaiya 2022.

- ^ Mannur 2017, pp. 411–420.

- ^ Hobdy 2020.

- ^ Idowu 2017.

- ^ Ryan 2017.

- ^ Medrano 2016.

- ^ Gopalakrishnan 2021.

- ^ Vanity Fair 2016, p. 144.

- ^ a b Safronova 2016.

- ^ Weatherford 2016.

- ^ The Irish Times 2019.

- ^ a b Pongsajapan 2017.

- ^ Shariatmadari 2012.

- ^ a b Augoye 2021.

- ^ Camminga 2020, p. 818.

- ^ a b c d e f Crockett 2017.

- ^ Useni 2014.

- ^ Malec 2017.

- ^ Flood 2019.

- ^ Dayo 2019.

- ^ Ring 2022.

- ^ a b Camminga 2020, p. 820.

- ^ Hubbard 2019.

Bibliography[edit]

- Abba, Abba A. (Winter 2021). "Remediating Biafra: Adichie's Half of a Yellow Sun as a Symbolic Vehicle of Postwar Reconciliation". Research in African Literatures. 51 (4). Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press: 1–17. doi:10.2979/reseafrilite.51.4.01. ISSN 0034-5210. OCLC 9144124984. Retrieved 2 May 2024. – via Project Muse (subscription required)

- Adichie, Amanda Ngozi (2000). "My Mother, the Crazy African". In Posse Review. Multi-Ethnic Anthology. San Francisco, California: Spectrum Publishers. Archived from the original on 31 March 2024.

- Adichie, Chimamanda Ngozi (15 September 2006). "Truth and Lies". The Guardian. London, UK. Archived from the original on 31 March 2024. Retrieved 31 March 2024.

- Adichie, Chimamanda Ngozi (3 May 2013). "Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie Chooses Ben Enwonwu's Tutu". Front Row. London, UK. BBC Radio 4. Archived from the original on 6 May 2013. Retrieved 18 January 2014.

- Adichie, Chimamanda Ngozi (20 February 2014). "Why Can't a Smart Woman Love Fashion?". Elle.com. New York City, New York: Hearst Magazines Digital Media. Archived from the original on 7 April 2024. Retrieved 29 April 2024.

- Agbo, Njideka (26 September 2018). "Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie: The Fearless Writer". The Guardian Nigeria. Lagos, Nigeria. Archived from the original on 3 April 2024. Retrieved 3 April 2024.

- Akinyoade, Akinwale (5 January 2021). "Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie Reveals How She Came about the Name 'Chimamanda'". The Guardian Nigeria. Lagos, Nigeria. Archived from the original on 25 April 2024. Retrieved 17 April 2024.

- Akyeampong, Emmanuel (2021). "Transformations in Global Blackness: African and African American Relations, c. 1960 to Recent Times". Transition (131). Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press: 78–95. doi:10.2979/transition.131.1.08. ISSN 0041-1191. OCLC 9368929313. Retrieved 4 May 2024.

- "'Americanah' Author Explains 'Learning' To Be Black in the U.S." Fresh Air. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: NPR. 27 June 2013. Archived from the original on 16 October 2019. Retrieved 24 March 2018.

- Aneasoronye, Modestus (17 June 2019). "Chimamanda Adichie Receives Her 11th Honorary Degree". Business Day. Lagos, Nigeria. Archived from the original on 7 May 2024. Retrieved 7 May 2024.

- "Announcing the National Book Critics Awards Finalists for Publishing Year 2013". bookcritics.org. New York City, New York: National Book Critics Circle. 14 January 2014. Archived from the original on 15 January 2014. Retrieved 14 January 2014.

- Anthony, Joseph (9 April 2023). "Exploring the Literary Genius of Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie". Herald Nigeria. Archived from the original on 27 March 2024. Retrieved 27 March 2024.

- Anya, Ike (15 October 2005). "In the Footsteps of Achebe: Enter Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie". African Writer. Williamstown, New Jersey: African Writer Magazine. Archived from the original on 4 October 2023. Retrieved 31 March 2024.

- Augoye, Jayne (2 January 2021). "Why I Stopped Attending Catholic Churches in Nigeria — Chimamanda Adichie". Premium Times. Abuja, Nigeria. Archived from the original on 9 May 2024. Retrieved 9 May 2024.

- Ayo-Aderele, Adesola (12 April 2017). "Chimamanda Elected into US Academy of Arts and Science". The Punch. Lagos, Nigeria. Archived from the original on 26 January 2022. Retrieved 8 February 2021.

- Bhuta, Aishwarya (June 2018). "Book Review: Adichie, C.N., Dear Ijeawele, or a Feminist Manifesto in Fifteen Suggestions, London: Fourth Estate, 2017. 80 pages, ₹250. ISBN: 9780008241032". Indian Journal of Gender Studies. 25 (2). Thousand Oaks, California: SAGE Publications: 319–323. doi:10.1177/0971521518761445. ISSN 0971-5215. OCLC 7651369612. Retrieved 9 May 2024.(subscription required)

- Bragg, Beauty (Winter 2017). "Racial Identification, Diaspora Subjectivity, and Black Consciousness in Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie's Americanah and Helen Oyeyemi's Boy, Snow, Bird". South Atlantic Review. 82 (4). Tuscaloosa, Alabama: South Atlantic Modern Language Association: 121–138. ISSN 0277-335X. OCLC 9970616626. Retrieved 4 May 2024.

- Braimah, Ayodale (13 February 2018). "Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie (1977–)". BlackPast. Seattle, Washington: BlackPast.org. Archived from the original on 10 August 2022. Retrieved 16 August 2022.

- Brockes, Emma (4 March 2017). "Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie: 'Can people please stop telling me feminism is hot?'". The Guardian. London, UK. Archived from the original on 3 September 2019. Retrieved 22 August 2017.

- Broom, Sarah M. (9 May 2021). "Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie: 'My Madness Will Now Bare Itself'". The New York Times. New York City, New York. Archived from the original on 2 May 2024. Retrieved 30 April 2024.

- Busby, Margaret (3 February 2017). "Buchi Emecheta Obituary". The Guardian. London, UK. Archived from the original on 4 February 2017. Retrieved 14 November 2020.

- Camminga, B. (July 2020). "Disregard and Danger: Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie and the Voices of Trans (And Cis) African Feminists". The Sociological Review. 68 (4). Thousand Oaks, California: Sage Publishing: 817–833. doi:10.1177/0038026120934695. ISSN 0038-0261. OCLC 8643495664. Retrieved 8 May 2024. – via SAGE Journals (subscription required)

- Carotenuto, Silvana (2017). "12. 'A Kind of Paradise' Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie's Claim to Agency, Responsibility & Writing" (PDF). In Ememyonu, Ernest N. (ed.). A Companion to Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie. Woodbridge, Suffolk: James Currey. pp. 169–184. ISBN 978-1-84701-162-6.

- "Chimamanda Adichie – Quintessence of a Literary Icon". Leadership. Abuja, Nigeria. AllAfrica. 5 August 2018. Gale A550692546. Retrieved 6 May 2024.(subscription required)

- "Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, a Pride to Africa, a Treasure to the World". Business Day. 24 June 2016. Archived from the original on 23 March 2024. Retrieved 23 March 2024.

- "Chimamanda's Mother for Burial May 1". This Day. Apapa, Lagos. 16 March 2021. Archived from the original on 22 May 2022. Retrieved 12 March 2022.

- "Chimamanda to Receive 16th Honorary PhD from the Catholic University of Louvain Belgium". The Guardian Nigeria. Lagos, Nigeria. 22 March 2022. Archived from the original on 22 March 2022. Retrieved 22 March 2022.

- Chutel, Lynsey (3 July 2016). "Award-Winning Author Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie Has Had a Baby, Not That It's Anyone's Business". Quartz. New York City, New York: G/O Media. Archived from the original on 4 July 2016. Retrieved 3 July 2016.

- Crockett, Emily (15 March 2017). "The Controversy over Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie and Trans Women, Explained". Vox. Washington, D.C.: Vox Media. Archived from the original on 25 March 2024. Retrieved 9 May 2024.

- "Curriculum Vitae: Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie". A & S Magazine. Vol. 13, no. 1. Baltimore, Maryland: Zanvyl Krieger School of Arts & Sciences, Johns Hopkins University. Fall 2015. Archived from the original on 2 October 2023. Retrieved 1 April 2024.

- Daniels, Juliana (2022). "Alternative Feminism: Interrogating Marriage and Motherhood in Chimamanda Ngozie Adichie's Half of a Yellow Sun and Purple Hibiscus". The International Journal of Humanities Education. 21 (1). Champaign, Illinois: Common Ground Research Network, University of Illinois: 53–66. doi:10.18848/2327-0063/CGP/v21i01/53-66. ISSN 2327-0063. OCLC 9695413750. ProQuest 2743806195.(subscription required)

- Day, Elizabeth (15 April 2013). "Americanah by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie – Review". The Guardian. London, UK. Archived from the original on 16 April 2024. Retrieved 22 April 2024.

- Dayo, Bernard (28 May 2019). "Read Chimamanda Adichie's Elegantly Moving Tribute to Binyavanga Wainaina and Cry with Us". YNaija. Lagos, Nigeria: Generation Y!. Archived from the original on 21 August 2020. Retrieved 23 March 2024.

- Dube, Musa W. (April 2019). "Purple Hibiscus: A Postcolonial Feminist Reading". Missionalia. 46 (2). Stellenbosch, Western Cape, South Africa: Stellenbosch University: 222–235. doi:10.7832/46-2-311. ISSN 0256-9507. OCLC 8081262364.

- Edeme, Victoria (7 October 2022). "Chimamanda Adichie Receives Harvard's Highest Honour". The Punch. Lagos, Nigeria. Archived from the original on 5 May 2024. Retrieved 5 May 2024.

- Egbunike, Louisa Uchum (2017). "1. Narrating the Past: Orality, History & the Production of Knowledge in the Works of Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie". In Ememyonu, Ernest N. (ed.). A Companion to Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie. Woodbridge, Suffolk: James Currey. pp. 15–30. ISBN 978-1-84701-162-6.

- Ejikeme, Anene (2017). "The Women of Things Fall Apart, Speaking from a Different Perspective: Chimamanda Adichie's Headstrong Storytellers". Meridians. 15 (2). Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Press: 307–329. ISSN 1536-6936. OCLC 8870766018. Retrieved 1 May 2024. – via Project Muse (subscription required)

- Felperin, Leslie (11 October 2013). "Half of a Yellow Sun: London Review". The Hollywood Reporter. Los Angeles, California: Penske Media Corporation. Archived from the original on 20 November 2023. Retrieved 23 April 2024.

- Flood, Alison (11 February 2021). "Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie to Publish Memoir about Her Father's Death". The Guardian. London, UK. Archived from the original on 16 September 2023. Retrieved 27 February 2021.

- Flood, Alison (22 May 2019). "Binyavanga Wainaina, Kenyan Author and Gay Rights Activist, Dies Aged 48". The Guardian. London, UK. Archived from the original on 28 June 2023. Retrieved 9 May 2024.

- Flood, Alison (14 March 2014). "Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie Wins US National Book Critics Circle Award". The Guardian. London, UK. Archived from the original on 16 January 2024. Retrieved 7 May 2024.

- Forna, Aminatta (16 May 2009). "Endurance Tests". The Guardian. London, UK. Archived from the original on 5 January 2024. Retrieved 22 April 2024.

- Gopalakrishnan, Manasi (9 September 2021). "Merkel Speaks with Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie". Deutsche Welle. Bonn, Germany. Archived from the original on 9 October 2023. Retrieved 9 May 2024.

- Greenberg, Zoe (15 March 2017). "Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie's Blueprint for Feminism". The New York Times. New York City, New York. Archived from the original on 15 June 2018. Retrieved 22 March 2024.

- Hewett, Heather (May 2005). "Coming of Age: Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie and the Voice of the Third Generation". English in Africa. 32 (1). Makhanda, South Africa: Rhodes University: 73–97. ISSN 0376-8902. OCLC 5878056558. Retrieved 30 April 2024.

- Hobdy, Dominique (26 October 2020). "Why 'Americanah' Author Chimamanda Ngozi Is All About Nigerian Designers". Essence.com. New York City, New York: Essence Communications. Archived from the original on 7 May 2024. Retrieved 9 May 2024.

- Hubbard, Ladee (10 May 2019). "Power to Define Yourself: The Diaspora of Female Black Voices". The Times Literary Supplement. London, UK: The Times Literary Supplement Ltd. ISSN 0307-661X. Archived from the original on 1 October 2020. Retrieved 14 September 2020.

- Ibeh, Chukwuebuka (7 April 2022). "Chimamanda Adichie Debuts Children's Book Under the Pseudonym Nwa Grace James". Brittle Paper. Chicago, Illinois: Ainehi Edoro. Archived from the original on 1 April 2023. Retrieved 1 April 2023.

- Idowu, Torera (9 May 2017). "This Is Why Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie Is Only Wearing Nigerian Brands". CNN. Atlanta, Georgia. Archived from the original on 7 May 2024. Retrieved 9 May 2024.

- Igwe, Chidi, ed. (Winter 2017). "Profile: Professor Ernest Nneji Ememyonu" (PDF). ISA Newsletter. 4 (1). Milwaukee, Wisconsin: Igbo Studies Association: 7–10. ISSN 2375-9720. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 April 2024. Retrieved 2 May 2024.

- Irvine, Lindesay (24 September 2008). "Adichie Wins a $500,000 Genius Grant". The Guardian. London, UK. Archived from the original on 22 March 2024. Retrieved 22 March 2024.

- Ishaya, Yusuf Tsojon; Gunn, Michael (March 2022). "Graphology as Style in Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie's The Thing Around Your Neck". LWATI: A Journal of Contemporary Research. 19 (1). Beijing, China: Universal Academic Services: 69–86. ISSN 1813-2227. Archived from the original on 9 November 2022.

- Italie, Hillel (30 June 2014). "Tartt, Goodwin Awarded Carnegie Medals". The Seattle Times. Seattle, Washington. Associated Press. Archived from the original on 15 July 2014. Retrieved 1 July 2014.

- "James Nwoye Adichie (1932 – 2020)". The Sun. Lagos, Nigeria. 3 July 2020. Archived from the original on 22 May 2022. Retrieved 20 May 2021.

- Jaschik, Scott (28 February 2016). "Debate at Barnard over Selection of Commencement Speaker". Inside Higher Ed. Washington, D.C. Archived from the original on 7 May 2024. Retrieved 7 May 2024.

- Jones, Radhika (16 April 2015). "Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie: The World's 100 Most Influential People". Time. New York City, New York: Time Inc. Archived from the original on 20 November 2015. Retrieved 14 December 2015.

- Jordan, Atiya (24 March 2022). "Writer Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie to Accept 16th Honorary Degree". Black Enterprise. New York City, New York: Earl G. Graves Publishing Company. Archived from the original on 7 May 2024. Retrieved 7 May 2024.

- Krug, Nora (12 September 2003). "Chimamanda Adichie's Children's Book Has No Agenda beyond Joy". The Washington Post. Washington, D.C. Archived from the original on 20 December 2023. Retrieved 5 April 2024.

- Law, Katie (29 October 2020). "Zikora: A Short Story by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, Review: A Taut Tale of Sexism and Single Motherhood". Evening Standard. London, UK. Archived from the original on 7 April 2023. Retrieved 6 November 2020.

- Lee, Nicole (11 May 2015). "Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie: 'Fear of Causing Offence Becomes a Fetish'". The Guardian. London, UK. Archived from the original on 2 November 2023. Retrieved 23 April 2024.

- Lozada, Carlos (6 May 2021). "In Grieving for Her Father, a Novelist Discovers the Failure of Words". The Washington Post. Washington, D.C. Archived from the original on 18 June 2021. Retrieved 17 June 2021.

- Luebering, J. E. (30 April 2024). "Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie: Nigerian Author". Britannica.com. Chicago, Illinois: Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 23 April 2024. Retrieved 30 April 2024.

- MacFarquhar, Larissa (28 May 2018). "Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie Comes to Terms with Global Fame". New Yorker.com. New York City, New York: Advance Publications. Archived from the original on 5 March 2021. Retrieved 17 June 2021.

- Madueke, Sylvia Ijeoma (August 2019). "On Translating Postcolonial African Writing: French Translation of Chimamanda Adichie's Half of a Yellow Sun". TranscUlturAl. 11 (1). Edmonton, Alberta: University of Alberta: 49–66. doi:10.21992/tc29446. ISSN 1920-0323. OCLC 8615550149.

- Majendie, Paul (9 August 2007). "Nigerian Author Wins Top Women's Fiction Prize". London, UK. Reuters. Archived from the original on 2 August 2023. Retrieved 7 May 2024.

- Malec, Jennifer (26 July 2017). "Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie Pays Touching Tribute to Binyavanga Wainaina: 'A great and rare and genuine talent'". The Johannesburg Review of Books. Johannesburg, South Africa: Ben Williams Publishing. Archived from the original on 2 December 2020. Retrieved 21 February 2021.

- Mannur, Anita (June 2017). "The Danger of a Singular Fashion: Studies of Race, Fashion, and Beauty in American Studies". American Quarterly. 69 (2). Baltimore, Marylan: Johns Hopkins University Press: 411–420. doi:10.1353/aq.2017.0034. ISSN 0003-0678. OCLC 7075078562. JSTOR 26360860. Retrieved 9 May 2024. – via Project Muse (subscription required)

- Martin, Michel (18 March 2014). "Feminism Is Fashionable for Nigerian Writer Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie". Tell Me More. Washington, D.C.: NPR. Archived from the original on 28 September 2019. Retrieved 5 April 2018.

- Mbah, Victor Chukwudi (2015). "Themes and Techniques in African Novel: A Review of Ngozi Chimamanda Adichie's Half of a Yellow Sun". Ansu Journal of Language and Literary Studies. 1 (2). Uli, Anambra, Nigeria: Chukwuemeka Odumegwu Ojukwu University: 345–359. ISSN 2465-7352. Archived from the original on 16 November 2023. Retrieved 28 April 2024.

- McGrath, Charles (8 October 2006). "No Life Away from Her Books". The Age. Melbourne, Australia. New York Times Agency. Archived from the original on 16 April 2024. Retrieved 22 April 2024.

- Medrano, Kastalia (1 December 2016). "Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie Continues To Be the Hero We Need". Time. New York City, New York: Time Inc. Archived from the original on 20 December 2023. Retrieved 9 May 2024.

- "Meghan Markle Puts Sinéad Burke on the Cover of Vogue's September Issue". The Irish Times. Dublin, Ireland. 29 July 2019. Archived from the original on 29 July 2019. Retrieved 31 July 2019.

- Mullane, Janet (2014). "Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie". In Trudeau, Lawrence J. (ed.). Contemporary Literary Criticism. Vol. 364. Farmington Hills, Michigan: Cengage Learning. ISBN 978-1-4144-9987-1.

- Murray, Senan (8 June 2007). "The New Face of Nigerian Literature?". BBC News. Abuja, Nigeria. Archived from the original on 22 November 2022. Retrieved 26 August 2022.

- Mwakikagile, Godfrey (2001). Ethnic Politics in Kenya and Nigeria. Huntington, New York: Nova Science Publishers. ISBN 978-1-56072-967-9.

- Ndula, Janet (2017). "2. Deconstructing Binary Oppositions of Gender in Purple Hibiscus : A Review of Religious/Traditional Superiority & Silence". In Ememyonu, Ernest N. (ed.). A Companion to Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie. Woodbridge, Suffolk: James Currey. pp. 31–44. ISBN 978-1-84701-162-6.

- "Notes on Grief by Chimamanda Ngozi Adiche". Kirkus Reviews.com. New York City, New York: Kirkus Media. 11 May 2021. Archived from the original on 25 March 2024. Retrieved 29 April 2024.

- Nwankwọ, Izuu (2023). "Traditions of Naming in Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie's Fiction". Postcolonial Text. 18 (3). Villetaneuse, France: Sorbonne Paris North University: 1–17. ISSN 1705-9100. Archived from the original on 30 March 2024.

- Obi-Young, Otosirieze (15 October 2018). "Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie's Purple Hibiscus Turns 15: The Best Moments of a Modern Classic". Brittle Paper. Chicago, Illinois: Ainehi Edoro. Archived from the original on 27 March 2024. Retrieved 27 March 2024.

- Obi-Young, Otosirieze (20 September 2021). "Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie Is in a Different Place Now". Open Country Mag. Lagos, Nigeria. Archived from the original on 2 June 2023. Retrieved 31 March 2024.

- Obi-Young, Otosirieze (4 April 2022). "Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie's Children's Picture Book Coming in 2023". Open Country Mag. Lagos, Nigeria. Archived from the original on 1 April 2023. Retrieved 1 April 2023.

- Olaiya, Tope Templer (13 October 2022). "Chimamanda Adichie Did Not Accept National Honour, Team Confirms". The Guardian Nigeria. Lagos, Nigeria. Archived from the original on 2 August 2023. Retrieved 14 October 2022.

- Okachie, Leonard (19 May 2011). "Chimamanda Selected as Radcliffe Fellow". Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study News. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University. Archived from the original on 16 October 2019. Retrieved 16 January 2017.

- Okolo, Luke Ndudi (2016). "Thematic and Stylistic Analysis of Chimamanda Adichie's Purple Hibiscus". Ansu Journal of Language and Literary Studies. 1 (3). Uli, Anambra, Nigeria: Chukwuemeka Odumegwu Ojukwu University: 1–13. ISSN 2465-7352. Archived from the original on 24 March 2024. Retrieved 23 April 2024.

- Olaopa, Tunji (27 November 2022). "An Encounter with Toyin Falola: Between Celebration and Canonization of Intellectuals". This Day. Apapa, Lagos. Archived from the original on 4 December 2022. Retrieved 4 December 2022.

- Ordu, Stanley (December 2021). "Womanism and Patriarchy in Chimamanda Adichie's Purple Hibiscus" (PDF). Litinfinite Journal. 3 (2). Kolkata, India: Supriyo Chakraborty Penprints Publications: 61–73. doi:10.47365/litinfinite.3.2.2021.61-73. ISSN 2582-0400. OCLC 9455975886. Retrieved 3 May 2022.

- Pongsajapan, Robert (17 March 2017). "Award-Winning Author Adichie Explores Faith, Feminism at Georgetown Event". Georgetown University News. Washington, D.C.: Georgetown University. Archived from the original on 1 October 2023. Retrieved 9 May 2024.

- "Previous Winners". Caine Prize. London, UK: The Caine Prize for African Writing. 2009. Archived from the original on 12 December 2009.

- Richardson, Catherine (January–February 2011). "Dayton Literary Peace Prize". Poets & Writers Magazine. Vol. 39, no. 1. New York City, New York: Poets & Writers Inc. ISSN 0891-6136. Gale A247445488. Retrieved 7 May 2024.(subscription required)

- Ring, Trudy (2 December 2022). "Novelist Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie Goes Anti-Trans Again". Advocate.com. Los Angeles, California: Pride Media. Archived from the original on 10 May 2024. Retrieved 9 May 2024.

- Roifah, Miftahur (October 2021). "Becoming a Mother: The Transition to Motherhood in Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie's 'Zikora'". Prosodi. 15 (2). Bangkalan, Indonesia: University of Trunojoyo Madura: 178–185. doi:10.21107/prosodi.v15i2.12184. ISSN 1907-6665. Retrieved 3 May 2024.

- Ryan, Lisa (8 May 2017). "Here's Why Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie Is Wearing Only Nigerian Brands". The Cut. New York City, New York: New York Magazine. Archived from the original on 5 December 2023. Retrieved 9 May 2024.

- Safronova, Valeriya (28 November 2016). "Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie Talks Beauty, Femininity and Feminism". The New York Times. New York City, New York. Archived from the original on 22 March 2024. Retrieved 9 May 2024.

- Sam-Duru, Prisca (22 January 2014). "Chimamanda Adichie, a Growing Literary Prodigy". Vanguard. Lagos, Nigeria. Archived from the original on 2 August 2023. Retrieved 23 April 2024.

- Sebola, Moffat (May 2022). "Some Reflections on Selected Themes in Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie's Fiction and Her Feminist Manifesto". Literator. 43 (1). Potchefstroom, South Africa: Bureau for Scholarly Journals. doi:10.4102/lit.v43i1.1723. ISSN 0258-2279. OCLC 9627424976. Retrieved 4 May 2024.

- Sefa-Boakye, Jennifer (17 February 2015). "Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie Co-Curates PEN World Voices Festival in NYC with Focus on African Literature". PEN America. New York City, New York. Archived from the original on 2 November 2023. Retrieved 23 April 2024.

- Shariatmadari, David (13 January 2012). "Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie: Religious Leaders Must Help End Nigeria Violence". The Guardian. London, UK. Archived from the original on 29 January 2020. Retrieved 9 May 2024.

- Sharobeem, Heba M. (Spring 2015). "Space as the Representation of Cultural Conflict and Gender Relations in Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie's The Thing Around Your Neck". Rocky Mountain Review. 69 (1). Pullman, Washington: Rocky Mountain Modern Language Association: 18–36. doi:10.1353/rmr.2015.a580802. ISSN 1948-2825. OCLC 7791796472. Retrieved 1 May 2024. – via Project Muse (subscription required)

- Shilling, Jane (2 April 2009). "The Thing Around Your Neck by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie: Review". The Daily Telegraph. London, UK. Archived from the original on 29 March 2024. Retrieved 29 April 2024.

- Streeter, Leslie Gray (16 May 2021). "Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie's Notes on Grief Captures the Bewildering Messiness of Loss – Review". The Independent. London, UK. Archived from the original on 2 September 2023. Retrieved 23 April 2024.

- "The 10 Best Books of 2013". The New York Times. New York City, New York. 4 December 2013. Archived from the original on 18 April 2024. Retrieved 23 April 2024.

- "The 2016 International Best Dressed List". Vanity Fair. New York City, New York: Condé Nast. 1 October 2016. pp. 125–151. ISSN 0733-8899. Archived from the original on 24 April 2024. Retrieved 9 May 2024.

- "The Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie's Parents' Memoirs (2) Knowing Each Other before You Marry". The Sun. Lagos, Nigeria. 14 September 2019. Archived from the original on 1 April 2024. Retrieved 1 April 2024.